インターネットで蝉を追うLAFCADIO HEARN, SHADOWINGS

|

LAFCADIO HEARN,

SHADOWINGS,

Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1971

"Sémi"

(CICADAE)

Koé ni mina

Naki-shimôté ya —

Sémi no kara !

— Japanese Love-Song

The voice having been all consumede by crying, there remains only the shell of the sémi !

I

A CELEBRATED Chinese scholar, known in Japanese literature as Riku-Un, wrote the following quaint account of the Five Virtues of the Cicada : —

" I. — The Cicada has upon its head certain figures or signs1. These represent its [written] characters, style, Iiterature.

" II. — It eats nothing belonging to earth, and drinks only dew. This proves its cleanliness, purity, propriety.

" III. — It always appears at a certain fixed time. This proves its fidelity, sincerity, truthfulness.

" IV. — It will not accept wheat or rice. This proves its probity, uprightness, honesty.

" V. — It does not make for itself any nest to live in. This proves its frugality, thrift, economy."

〔1 The curious markings on the head of one variety of Japanese sémi are believed to be characters which are names of souls. 〕

We might compare this with the beautiful address of Anacreon to the cicada, written twenty-four hundred years ago : on more than one point the Greek poet and the Chinese sage are in perfect accord : —

"We deem thee bappy, O Cicada, because, having drunk, Iike a king, only a little dew, thou dost chirrup on the tops of trees. For all things whatsoever that thou seest in the fields are thine, and whatsoever the seasons bring forth. Yet art thou the friend of the tillers of the land, — from no one harmfully taking aught. By mortals thou art held in honor as the pleasant harbinger of summer ; and the Muses love thee. Phoebus himself loves thee, and has given thee a shrill song. And old age does not consume thee. O tbou gifted one, — earth-born, song-loving. free from pain, having flesh witbout blood, — thou art nearly equal to the Gods ! "2

〔2 In this and other citations from the Greek anthology, I have depended upon Burges' translation. 〕

And we must certainly go back to the oId Greek literature in order to find a poetry comparable to that of the Japanese on the subject of musical insects. Perhaps of Greek verses on the cricket, the most beautiful are the lines of Meleager : "O cricket, the soother of slumber ... weaving the thread of a voice that causes love to wander away !" ...There are Japanese poems scarcely less delicate in sentiment on the chirruping of night-crickets ; and Meleager's promise to reward the little singer with gifts of fresh leek, and with " drops of dew cut up small," sounds strangely Japanese. Then the poem attributed to Anyté, about the little girl Myro making a tomb for her pet cicada and cricket, and weeping because Hades, " hard to be persuaded," had taken her playthings away, represents an experience familiar to Japanese child-life. I suppose that little Myro — (how freshly her tears still glisten, after seven and twenty centuries !) — prepared that " common tomb " for her pets much as the little maid of Nippon would do to-day, putting a small stone on top to serve for a monument. But the wiser Japanese Myro would repeat over the grave a certain Buddhist prayer.

It is especially in their poems upon the cicada that we find the old Greeks confessing their love of insect-melody : witness the lines in the Anthology about the tettix caught in a spider's snare, and " making lament in the thin fetters " until freed by the poet ; — and the verses by Leonidas of Tarentum picturing the " unpaid minstrel to wayfaring men " as "sitting upon lofty trees, warmed with the great heat of summer, sipping the dew that is like woman's milk ; " — and the dainty fragment of Meleager, beginning : "Thou vocal tettix, drunk with drops of dew, sitting with thy serrated limbs upon the tops of petals, thou givest out the melody of the lyre from thy dusky skin."... Or take the charming address of Evenus to a nightingale : —

"Thou Attic maiden. honey-fed, hast chirping seized a chirping cicada. and bearest it to thy unfledged young. — thou, a twitterer. the twitterer, — thou, the winged, the well-winged, — thou, a stranger, the stranger, — thou, a summer-child, the summer-child ! Wilt thou not quickly cast it from thee ? For it is not right, it is not just, that those engaged in song should perish by tbe mouths of those engaged in song."

On the other hand, we find Japanese poets much more inclined to praise the voices of night-crickets than those of sémi. There are countless poems about sémi, but very few which commend their singing. Of course the sémi are very different from the cicadae known to the Greeks. Some varieties are truly musical ; but the majority are astonishingly noisy, — so noisy that their stridulation is considered one of the great aftlictions of summer. Therefore it were vain to seek among the myriads of Japanese verses on sémi for anything comparable to the lines of Evenus above quoted ; indeed, the only Japanese poem that I could find on the subject of a cicada caught by a bird, was the following : —

Ana kanashi !

Tobi ni toraruru

Sémi no koë.

— RANSETSU.

Ah ! how piteous the cry of the sémi seized by the kitet !

Or " caught by a boy " the poet might equally well have observed, — this being a much more frequent cause of the pitiful cry. The lament of Nicias for the tettix would serve as the elegy of many a sémi : —

"No more shall Idelight myself by sending out a sound from my quich-moving wings, because I have fallen into the savage hand of a boy, who seized me unexpectedly, as I was sitting under the green leaves."

Here I may remark that Japanese children usually capture sémi by means of a long slender bamboo tipped with bird-lime (mochi). The sound made by some kinds of sémi when caught is really pitiful, — quite as pitiful as the twitter of a terrified bird. One finds it diffcult to persuade oneself that the noise is not a voice of anguish, in the human sense of the word " voice," but the production of a specialized exterior membrane. Recently, on hearing a captured sémi thus scream, I became convinced in quite a new way that the stridulatory apparatus of certain insects must not be thought of as a kind of musical instrument, but as an organ of speech, and that its utterances are as intimately associated with simple forms of emotion, as are the notes of a bird, — the extraordinary difference being that the insect has its vocal chords outside. But the insect-world is altogether a world of goblins and fairies : creatures with organs of which we cannot discover the use, and senses of which we cannot imagine the nature ; — creatures with myriads of eyes, or with eyes in their backs, or with eyes moving about at the ends of trunks and horns ; — creatures with ears in their legs and bellies, or with brains in their waists ! If some of them happen to have voices outside of their bodies instead of inside, the fact ought not to surprise anybody.

l have not yet succeeded in finding any Japanese verses alluding to the stridulatory apparatus of sémi, — though I think it probable that such verses exist. Certainly the Japanese have been for centuries familiar with the peculiarities of their own singing insects. But I should not now presume to say that their poets are incorrect in speaking of the " voices " of crickets and of cicadae. The old Greek poets who actually describe insects as producing music with their wings and feet, nevertheless speak of the " voices," the " songs," and the " chirruping " of such creatures, — just as the Japanese poets do. For example, Meleager thus addresses the cricket :

"O thou that art with shrill wings tbe self-formed imitation of the lyre, chirrup me something pleasant while beatingyour vocal wings with your feet ! ... "

Il

BEFORE speaking further of the poetical literature of sémi, I must attempt a few remarks about the sémi themselves. But the reader need not expect anything entomological. Excepting, perhaps, the butterflies, the insects of Japan are still little known to men of science ; and all that I can say about sémi has been learned from inquiry, from personal observation, and from old Japanese books of an interesting but totally unscientific kind. Not only do the authors contradict each other as to the names and characteristics of the best-known sémi ; they attach the word sémi to names of insects which are not cicadae.

The following enumeration of sémi is certainly incomplete ; but I believe that it includes the better-known varieties and the best melodists. I must ask the reader, however, to bear in mind that the time of the appearance of certain sémi differs in different parts of Japan ; that the same kind of sémi may be called by different names in different provinces ; and that these notes have been written in Tôkyô.

I. — HARU-ZÉMI.

VARIOUS small sémi appear in the spring. But the first of the big sémi to make itself heard is the haru-zémi (" spring-sémi "), also called umazémi (" horse-sémi "), kuma-zémi (" bear-sémi "), and other names. It makes a shrill wheezing sound, — ji-i-i-i-i-iiiiiiii, — beginning low, and gradually rising to a pitch of painful intensity. No other cicada is so noisy as the haru-zémi ; but the life of the creature appears to end with the season. Probably this is the sémi referred to in an old Japanese poem : —

Hatsu-sémi ya !

" Koré wa atsui " to

lu hi yori.

— TAIMU.

The day after the first day on which we exclaim, " Oh, how hot it is ! " the first sémi begins to cry.

ll. — " SHINNÉ-SHINNÉ."

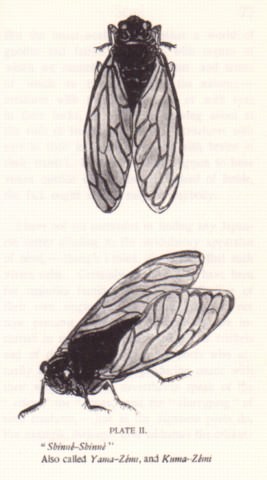

THE shinné-shinné — also called yama-zéimi, or " mountain-sémi " ; kuma-zémi, or " bear-sémi " ; and ô-sémi, or " great sémi " — begins to sing as early as May. It is a very large insect. The upper part of the body is almost black, and the belly a silvery-white ; the head has curious red markings. The name shinné-shinné is derived from the note of the creature, which resembles a quick continual repetition of the syllables shinné. About Kyôto this sémi is common : it is rarely heard in Tôkyô.

[My first opportunity to examine an ô-sémi was in Shidzuoka. Its utterance is much more complex than the Japanese onomatope implies ; I should liken it to the noise of a sewing-machine in full operation. There is a double sound : you hear not only the succession of sharp metallic clickings, but also, below these, a slower series of dull clanking tones. The stridulatory organs are light green, Iooking almost like a pair of tiny green leaves attached to the thorax.]

III. — ABURAZÉMI.

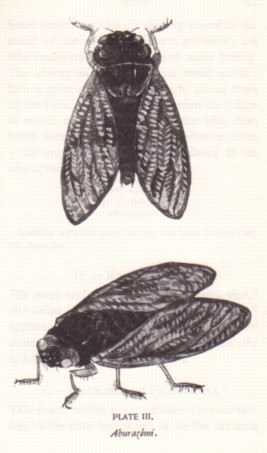

THE aburazémi, or "oil-sémi," makes its appearance early in the summer. I am told that it owes its name to the fact that its shrilling resembles the sound of oil or grease frying in a pan. Some writers say that the shrilling resembles the sound of the syllables gacharin-gacharin ; but others compare it to the noise of water boiling. The aburazémi begins to chant about sunrise ; then a great soft hissing seems to ascend from all the trees. At such an hour, when the foliage of woods and gardens still sparkles with dew, might have been composed the following verse, — the only one in my collection relating to the aburazémi : —

Ano koë dé

Tsuyu ga inochi ka ? —

Aburazémi !

Speaking with that voice, has the dew taken life ? — Only the aburazémi !

IV. — MUGI-KARI-ZÉMI.

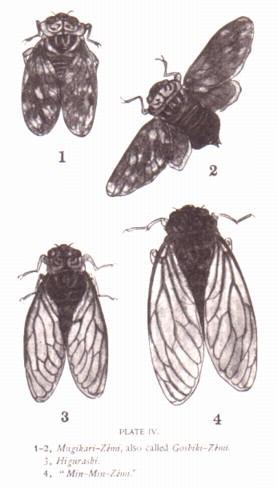

THE mugi-kari-zémi, or "barley-harvest sémi," also called goshiki-zémi, or "five-colored sémi," appears early in the summer. It makes two distinct sounds in different keys, resembling the syllables shi-in, shin — cbi-i, chi-i.

V. — HIGURASHI, OR " KANA-KANA."

THIS insect, whose name signifies "day-darkening," is the most remarkable of all the Japanese cicadae. It is not the finest singer among them ; but even as a melodist it ranks second only to the tsuku-tsuku-bôshi. It is the special minstrel of twilight, singing only at dawn and sunset ; whereas most of the other sémi make their music only in the full blaze of day, pausing even when rain-clouds obscure the sun. In Tôkyô the higurasbi usually appears about the end of June, or the beginning of July. Its wonderful cry, — kana-kana-kana-kana-kana, — beginning always in a very high clear key, and slowly descending, is almost exactly like the sound of a good hand-bell, very quickly rung. It is not a clashing sound, as of violent ringing ; it is quick, steady, and of surprising sonority. I believe that a single higurashi can be plainly heard a quarter of a mile away ; yet, as the old Japanese poet Yayû observed, " no matter how many higurashi be singing together, we never find them noisy." Though powerful and penetrating as a resonance of metal, the higurashi's call is musical even to the degree of sweetness ; and there is a peculiar melancholy in it that accords with the hour of gloaming. But the most astonishing fact in regard to the cry of the higurasbi is the individual quality characterizing the note of each insect. No two higurashi sing precisely in the same tone. If you hear a dozen of them singing at once, you will find that the timbre of each voice is recognizably different from every other. Certain notes ring like silver, others vibrate like bronze ; and, besides varieties of timbre suggesting bells of various weight and composition, there are even differences in tone, that suggest different forms of bell.

I have already said that the name higurashi means " day-darkening," — in the sense of twilight, gloaming, dusk ; and there are many Japanese verses containing plays on the word, — the poets affecting to believe, as in the following example, that the crying of the insect hastens the coming of darkness : —

Higurashi ya !

Sutétéoitémo

Kururu hi wo.

O Higurashi ! — even if you let it alone, day darkens tast enough !

This, intended to express a melancholy mood, may seem to the Western reader far-fetched. But another little poem — referring to the effect of the sound upon the conscience of an idler — will be appreciated by any one accustomed to hear the higurashi. I may observe, in this connection, that the first clear evening cry of the insect is quite as startling as the sudden ringing of a bell : —

Higurashi ya !

Kyô no kétai wo

Omou-toki.

— RIKEl.

Already, O Higurashi, your call announces the evening !

Alas, for the passing day, with its duties left undone !

VI. — " MlNMIN "-ZÉMI.

THE minmin-zémi begins to sing in the Period of Greatest Heat. It is called "min-min" because its note is thought to resemble the syllable "min" repeated over and over again, — slowly at first, and very loudly ; then more and more quickly and softly, till the utterance dies away in a sort of buzz: " min — min — min-min-min-minminmin-dzzzzzzz." The sound is plaintive, and not unpleasing. It is often compared to the sound of the voice of a priest chanting the sûtras.

VII. — TSUKU-TSUKU-B[O]SHI.

ON the day immediately following the Festival of the Dead, by the old Japanese calendar3

〔3 That is to say, upon the 16th day of the 7th month. 〕

(which is incomparably more exact than our Western calendar in regard to nature-changes and manifestations) , begins to sing the tsuku-tsuhu-bôshi. This creature may be said to sing like a bird. It is also called kutsu-kutse-bôshi, chôko-chôko-uisu, tsuku-tsuku-bôshi, tsuku-tsuku-oïshi, — all onomatopoetic appellations. The sounds of its song have been imitated in different ways by various writers. In lzumo the common version is. —

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu,

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu,

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu : —

Ui-ôsu

Ui-ôsu

Ui-ôsu

Ui-ôs-s-s-s-s-s-s-su.

Another version runs, —

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu,

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu,

Tsuku-tsuku-uisu : —

Chi-i yara !

Chi-i yara !

Chi-i yara !

Chi-i, chi, chi, chi, chi, chiii.

But some say that the sound is Tsukushi-koïshi. There is a legend that in old times a man of Tsukushi (the ancient name of Kyûshû) fell sick and died while far away from home, and that the ghost of him became an autumn cicada, which cries unceasingly, Tsuhushi-koïshi ! — Tsuhushi-koïshi ! (" I Iong for Tsukushi ! — l want to see Tsukushi ! " )

It is a curious fact that the earlier sémi have the harshest and simplest notes. The musical sémi do not appear until summer ; and the tsuku-tsuku-bôshi, having the most complex and melodious utterance of all, is one of the latest to mature.

VIII. — TSURIGANÉ-SÉMI.4

THE tsurigané-sémi is an autumn cicada. The word tsurigané means a suspended bell, — especially the big bell of a Buddhist temple. I am somewhat puzzled by the name ; for the insect's music really suggests the tones of a Japanese harp, or koto — as good authorities declare. Perhaps the appellation refers not to the boom of the bell, but to those deep, sweet hummings which follow after the peal, wave upon wave.

〔4 This sémi appears to be chiefly known in shikoku. 〕

Ill

JAPANESE poems on sémi are usually very brief ; and my collection chiefiy consists of hokku, — compositions of seventeen syllables. Most of these hokku relate to the sound made by the sémi, — or, rather, to the sensation which the sound produced within the poet's mind. The names attached to the following examples are nearly all names of old-time poets, — not the real names, of course, but the gô, or literary names by which artists and men of letters are usually known.

Yokoi Yayû, a Japanese poet of the eighteenth century, celebrated as a composer of hokku, has left us this naïve record of the feelings with which he heard the chirruping of cicadae in summer and in autumn : —

" In the sultry period, feeling opprcssed by the greatness of the heat, I made this verse : —

" Sémi atsushi

Matsu kirabaya to

Omou-madé.

[The chirruping of the sémi aggravates the heat until I wish to cut down the pine-tree on which it sings.]

" But the days passed quickly ; and later, when l heard the crying of the sémi grow fainter and fainter in the time of the autumn winds, I began to feel compassion for them, and I made this second verse : —

" Shini-nokoré

Hitotsu bakari wa

Aki no sémi."

[Now there survives

But a single one

Of the sémi of autumn !]

Lovers of Pierre Loti (the world's greatest prose-writer) may remember in Madame Chrysanthéme a delightful passage about a Japanese house, — describing the old dry woodwork as impregnated with sonority by the shrilling crickets of a hundred summers5; There is a Japanese poem containing a fancy not altogether dissimilar : —

〔5 Speaking of his own attempt to make a drawing of the interior, he observes " Il manque [a] ce logis dessiné son air fréle et sa sonorité de violon sec. Dans les traits de crayon qui représentent les boiseries, il n'y a pas la précision minutieuse avec laquelle elles sont ouvragées, ni leur antiquité extréme, ni leur propreté parfaite, ni les vibrations de cigales qu'elles semblent avoir emmagasinéespendant des centaines d'étes dans leurs fibres desséchées." 〕

Matsu no ki ni

Shimikomu gotoshi

Sémi no koë

Into the wood of the pine-tree

Seems to soak

The voice of the sémi.

A very large number of Japanese poems about Sémi describe the noise of the creatures as an affliction. To fully sympathize with the complaints of the poets, one must have heard certain varieties of Japanese cicadae in full midsummer chorus ; but even by readers without experience of the clamor, the following verses will probably be found suggestive : —

Waré hitori

Atsui yô nari, —

Sémi no koë !

— BUNS[O].

Meseems that only !, — I alone among mortals, —

Ever suffered such heat ! — oh, the noise of the sémi !

Ushiro kara

Tsukamu yô nari, —

Sémi no koë.

— JOF[U].

Oh, the noise of the sémi ! — a pain of invisible seizure, —

Clutched in an enemy's grasp, — caught by the hair from behind !

Yama no Kami no

Mimi no yamai ka ? —

Sémi no koë !

— TEIKOKU.

What ails the divinity's ears ? — how can the God of the Mountain

Suffer such noise to exist ? — oh, the tumult of sémi !

Soko no nai

Atsusa ya kumo ni

Sémi no koë !

— SAREN.

Fathomless deepens the heat : the ceaseless shrilling of sémi

Mounts, Iike a hissing of fire, up to the motionless clouds.

Mizu karété,

Sémi wo fudan-no

Taki no koë.

— GEN-U.

Water never a drop : the chorus of sémi, incessant,

Mocks the tumultuous ' hiss, — the rush and foaming of rapids.

Kagéroishi

Kumo mata satté,

Sémi no koë.

— KIT[O].

Gone, the shadowing clouds ! — again the shrilling of sémi

Rises and slowly swells, — ever increasing the heat !

Daita ki wa,

Ha mo ugokasazu, —

Sémi no koë !

— KAF[U].

Somewhere fast to the bark he clung ; but I cannot see him :

He stirs not even a leaf — oh ! the noise of that sémi !

Tonari kara

Kono ki nikumu ya !

Sémi no koë.

— CYUKAKU.

All because of the sémi that sit and shrill on its branches —

Oh ! how this tree of mine is hated now by my neighbor !

This reminds one of Yayû. We find another poet compassionating a tree frequented by Sémi : —

Kazé wa mina

Sémi ni suwarété,

Hito-ki kana !

— CH[O]SUI.

Alas ! poor solitary tree ! — pitiful now your lot, — every breath of air having been sucked up by the sémi !

Sometimes the noise of the sémi is described as a moving force : —

Sémi no koë

Ki-gi ni ugoité,

Kazé mo nashi !

--- SÔYÔ.

Every tree in the wood quivers with clamor of sémi :

Motion only of noise — never a breath of wind !

Také ni kité,

Yuki yori omoshi

Sémi no koë.

- TÔGETSU.

More heavy than winter-snow the voices of perching sémi :

See how the bamboos bend under the weight of their song ! 6

〔6 Japanese artists have found many a charming inspiration in the spectacle of bamboos bending under the weight of snow clinging to their tops. 〕

Morogoé ni

Yama ya ugokasu,

Ki-gi no sémi.

All shrilling together, the multitudinous sémi

Make, with their ceaseless clamor, even the mountain move.

Kusunoki mo

Ugoku yô nari,

Sémi no koë.

— BAIJAKU.

Even the camphor-tree seems to quake with the clamor of sémi !

Sometimes the sound is compared to the noise Of boiling water : —

Hizakari wa

Niétatsu sémi no

Hayashi kana !

In the hour of heaviest heat, how simmers the forest with sémi !

Niété iru

Mizu bakari nari —

Sémi no koë.

— TAIMU.

Simmers all the air with sibilation of sémi,

Ceaseless, wearying sense, — a sound of perpetual boiling.

Other poets complain especially Of the multitude of the nise-makers and the ubiquity of the noise : —

Aritaké no

Ki ni hibiki-kéri

Sémi no koë.

How many soever the trees, in each rings the voice of the sémi.

Matsubara wo

lchi ri wa kitari,

Sémi no koë.

— SENGA.

Alone I walked for miles into the wood of pine-trees :

Always the one same sémi shrilled its call in my ears.

Occasionally the subject is treated with comic exaggeratiOn : —

Naité iru

Ki yori mo futoshi

Sémi no koë.

The voice of the sémi is bigger [thicker] than the tree on which it sings.

Sugi takashi

Sarédomo sémi no

Amaru koë !

High though the cedar be, the voice of the sémi is incomparably higher !

Koé nagaki

Sémi wa mijikaki

Inochi kana !

How long, alas ! the voice and how short the life of the sémi !

Some poets celebrate the negative form of pleasure following upon the cessation of the sound : —

Sémi ni dété,

Hotaru ni modoru, —

Suzumi kana !

— YAY[U].

When the sémi cease their noise, and the fieflies come out — oh ! how refreshing the hour !

Sémi no tatsu,

Ato suzushisa yo !

Matsu no koë.

— BAIJAKU.

When the sémi cease their storm, oh, how refreshing the stillness !

Gratefully then resounds the musical speech of the pines.

[Here I may mention, by the way, that there is a little Japanese song about the matsu no koë, in which the onomatope " zazanza " very well represents the deep humming of the wind in the pine-needles : —

Zazanza !

Hama-matsu no oto wa, —

Zazanza,

Zazanza !

Zazanza !

The sound of the pines of the shore, —

Zazanza !

Zaranza ! ]

There are poets, however, who declare that the feeling produced by the noise of sémi depends altogether upon the nervous condition of the listener : —

Mori no sémi

Suzushiki koë ya,

Atsuki koë.

— OTSUSHU.

Sometimes sultry the sound ; sometimes, again, refreshing :

The chant of the forest-sémi accords with the hearer's mood.

Suzushisa mo

Atsusa mo sémi no

Tokoro kana !

— FUHAKU.

Sometimes we think it cool, — the resting-place of the svmi ; — sometimes we think it hot (it is all a matter of fancy ).

Suzushii to

Omoéba, suzushi

Sémi no koë.

— GINK[O].

If we think it is cool, then the voice of the sémi is cool (that is, the fancy changes the feeling).

In view of the many complaints of Japanese poets about the noisiness of sémi, the reader may be surprised to learn that out of sémi-skins there used to be made in both China and Japan — perhaps upon homoepathic principles — a medicine for the cure of ear-ache !

One poem, nevertheless, proves that sémi-music has its admirers : —

Omoshiroi zo ya,

Waga-ko no koë wa

Takai mori-ki no

Sémi no koë ! 7

Sweet to the ear is the voice of one's own child as the voice of a sémi perched on a tall forest tree. 〔7 There is another version of this poem : —

Omoshiroi zo ya,

Waga-ko no naku wa

Sembu-ségaki no

Kyô yori mo !

" More sweetly sounds the crying of one's own child than even the chanting of the sûtra in the service for the dead." The Buddhist service alluded to is held to be particularly beautiful. 〕

But such admiration is rare. More frequently the sémi is represented as crying for its nightly repast of dew : —

Sémi wo kiké, —

lchi-nichi naité

Yoru no tsuyu.

— KIKAKU.

Hear the sémi shrill ! So, from earliest dawning,

All the summer day he cries for the dew of night.

Yû-tsuyu no

Kuchi ni iru madé

Naku sémi ka ?

— BAISHITSU.

Will the sémi continue to cry till the night-dew ffills its mouth ?

Occasionally the sémi is mentioned in love-songs of which the following is a fair specimen. It belongs to that class of ditties commonly sung by geisha. Merely as a conceit, I think it pretty, in spite of the factitious pathos ; but to Japanese taste it is decidedly vulgar. The allusion to beating implies jealousy : —

Nushi ni tatakaré,

Washa matsu no sémi

Sugaritsuki-tsuki

Naku bakari !

Beaten by my jealous lover, —

Like the sémi on the pine-tree

I can only cry and cling !

And indeed the following tiny picture is a truer bit of work, according to Japanese art-principles (1 do not know the author's name) : —

Sémi hitotsu

Matsu no yû-hi wo

Kakaé-kéri.

Lo ! on the topmost pine, a solitary cicada

Vainly attempts to clasp one last red beam of sun.

IV

PHILOSOPHICAL verses do not form a numerous class of Japanese poems upon sémi ; but they possess an interest altogether exotic. As the metamorphosis of the butterfly supplied to old Greek thought an emblem of the soul's ascension, so the natural history of the cicada has furnished Buddhism with similitudes and parables for the teaching of doctrine.

Man sheds his body only as the sémi sheds its skin. But each reincamation obscures the memory of the previous one : we remember our former existence no more than the sémi remembers the shell from which it has emerged. Often a sémi may be found in the act of singing beside its cast-off skin ; therefore a poet has written : —

Waré to waga

Kara ya tomurô —

Sémi no koë.

— YAY[U].

Methinks that sémi sits and sings by his former body, —

Chanting the funeral service over his own dead self.

This cast-off skin, or simulacrum, — clinging to bole or branch as in life, and seeming still to stare with great glazed eyes, — has suggested many things both to profane and to religious poets. In love-songs it is often likened to a body consumed by passionate longing. In Buddhist poetry it becomes a symbol of earthly pomp, — the hollow show of human greatness : —

Yo no naka yo

Kaéru no hadaka,

Sémi no kinu !

Naked as frogs and weak we enter this life of trouble ;

Shedding our pomps we pass : so sémi quit their skins.

But sometimes the poet compares the winged and shrilling sémi to a human ghost, and the broken shell to the body left behind : —

Tamashii wa

Ukiyo ni naité,

Sémi no kara.

Here the forsaken shell : above me the voice of the creature

Shrills like the cry of a Soul quitting this world of pain.

Then the great sun-quickened tumult of the cicadae — Iandstorm of summer life foredoomed so soon to pass away — is likened by preacher and poet to the tumult of human desire. Even as the sémi rise from earth, and climb to warmth and light, and clamor, and presently again return to dust and silence, — so rise and clamor and pass the generations of men : —

Yagaté shinu

Keshiki wa miézu,

Sémi no koë.

— BASH[O].

Never an intimation in all those voices of sémi

How quickly the hush will come, — how speedily all must die.

I wonder whether the thought in this little verse does not interpret something of that summer melancholy which comes to us out of nature's solitudes with the plaint of insect-voices. Unconsciously those millions of millions of tiny beings are preaching the ancient wisdom of the East, — the perpetual Sûtra of Impermanency.

Yet how few of our modern poets have given heed to the voices of insects !

Perhaps it is only to minds inexorably haunted by the Riddle of Life that Nature can speak today, in those thin sweet trillings, as she spake of old to Solomon.

The Wisdom of the East hears all things. And he that obtains it will hear the speech of insects, — as Sigurd, tasting the Dragon's Heart, heard suddenly the talking of birds.

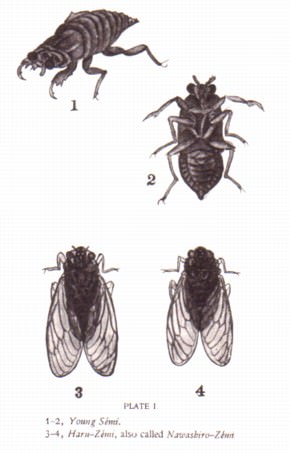

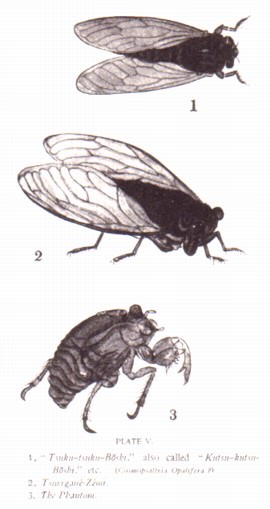

NOTE. — For the pictures of sémi accompanying this paper, I am indebted to a curious manuscript work in several volumes, preserved in the Imperial Library at Uyéno. The work is entitled Chûfu-Zusetsu, — which might be freely rendered as " Pictures and Descriptions of Insects," — and is dlvided into twelve books. The writer's name is unknown ; but he must have been an amiable and interesting person, to judge from the naïve preface which he wrote, apologizing for the labors of a lifetime. " When I was young," he says, " I was very fond of catching worms and insects, and making pictures of their shapes, — so that these pictures have now become several hundred in number." He believes that he has found a good reason for studying insects : "Among the multitude of living creatures in this world," he says, "those having large bodies are familiar : we know very well their names, shapes, and virtues, and the poisons which they possess. But there remain very many small creatures whose natures are stili unknown, notwithstanding the fact that such litfle beings as insects and worms are abie to injure men and to destroy what has value. So I think that it is very important for us to learn what insects or worms have special virtues or poisons." It appears that he had sent to him " from other countries " some kinds of insects " that eat the leaves and shoots of trees ; " but he could not " get their exact names." For the names of domesttc insects, he consulted many Chinese and Japanese books, and has been " able to wrlte the names with the proper Chlnese characters ; " but he tells us that he did not taii " to pick up also the names given to worms and tnsects by old farmers and little boys." The preface is dated thus : — "Ansei Kanoté, the third month — at a little cottage" [1856].

With the introduction of scientific studies the author of the Chûfu-Zusets could no longer hope to attract attention. Yet his very modest and very beautiful work was forgotten only a moment. It is now a precious curiosity ; and the old man's ghost mtght to-day find some happiness in a vtsit to the Imperial Library.

//END

Barbaroi!

Barbaroi!